Thursday, March 26, 2020

This article was written by Spring Intern Kaitlyn Carpenter

Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor was once called the dirtiest water in America. Raw sewage, runoff of the streets, heavy metals, and excess nutrients were found in the waters. This caused all sorts of problems for the people of Boston’s health and safety. With the MWRA implementing Deer Island Sewage Treatment Plant, thanks to ratepayers, Boston Harbor is now known as, “A Great American Jewel.” Harbor waters are cleaner with people enjoying beaches and recreating.

Nitrogen as a pollutant

Nitrogen is the worst pollutant of the oceans. It is a limiting nutrient in saltwater, and comes from sources like septic and sewage, agriculture, and lawns with synthetic fertilizers. Synthetic fertilizers need to be applied to lawns multiple times a year and in great quantities. All of that fertilizer does not make it into the soil. When it rains, it gets washed away into rivers, oceans, and sediment where it becomes a problem. Heavy rainfall can sweep septic, sewage, and agriculture nitrogen into waters too.

The areas that these come from are point and nonpoint sources. A point source is a source where we can pinpoint exactly where the pollution is coming from. While nonpoint sources do not have an exact location. CSOs (combined sewer overflows) are a point source for nitrogen pollution. CSOs become overwhelmed with stormwater runoff from heavy rains and discharge into the harbor. Parking lot, street, lawn, and agriculture runoff are nonpoint sources.

In 2011, the Boston Harbor Project opened the South Boston CSO Storage Tunnel. It stretches along the South Boston Waterfront about 27 feet underground. It is not actually a tunnel, not like the “Big Dig” that you can drive through. It’s called a tunnel because it is a 2.1 mile long, 17 foot in diameter tube structure. When there is heavy rain, this massive water storage unit can hold 19 million gallons of combined sewer and rain until a storm is over. Then, pumps the water to the Deer Island Treatment Plant at a sustainable rate for the facility to treat it.

When nitrogen enters the ocean in large amounts, phytoplankton will feed on it and grow like crazy! This creates that green scum we can see where oceans meet the land which is called an algal bloom. Algal blooms then lead to a process called eutrophication. Once that thick layer of algae appears on the surface. Algae grow quickly and they die. Whatever is left for oxygen, bacteria use up the O2 when they consume the algae and produce carbon dioxide. Now we are at a stage where the water has no oxygen, or it is hypoxic, which cannot sustain life. Fish, crabs, and other organisms become unhealthy or die due to the lack of oxygen- referred to as an ocean dead zone.

Nitrogen also enters the harbor from the major rivers that run through the Boston area: the Mystic, Charles, and Neponset. The most notable issue regarding nitrogen pollution is the menhaden and striped bass fish kill in the summer of 2018. Thousands of menhaden were chased up the river by the striped bass but entered a dead zone causing the fish to die. Their bodies could be seen floating at the surface at the Amelia Earhart dam by the Mystic River Bridge.

Currently, the MWRA is planning to make nitrogen removal facilities at Deer Island. While planning they have to monitor the different species of nitrogen that are discharged from the facility: ammonia-nitrogen (NH3¯), nitrites (NO2¯), nitrate (NO3¯), and total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN). Until that is created, the bacteria in the sediments will continue to work at the nitrogen. Turning it into gas expelling it from the harbor floor

Building Boston Harbor wastewater treatment plants to clear the waters

When the sediment waters of Boston Harbor became cleaner, marine organisms like tube-building amphipods were able to colonize. These small shrimp-like crustaceans are tiny but are a major player in the microbial fauna of benthic ecosystems. Before the Boston Harbor Project in 1991, amphipods were sparsely distributed. 5% of the harbor bottom was covered in a mat of tube-building amphipods.

From 1992-1994 sludge disposal stopped going into the harbor. After that, the amphipod Ampelisca spp bloomed along the harbor floor. 61% of the harbor bottom was covered in Ampelisca spp.

Full primary treatment was implemented at Deer Island between 1995-1997. Also, 7 CSOs have been eliminated. Peak Ampelisca spp mat coverage at 64% of the bottom at the time covered the floor.

During the years of 1998-2000 full secondary treatment was implemented. Nut Island now transfers its treated wastewater to Deer Island. 2 more CSOs have been eliminated. Ampelisca spp mats decline to 33%. Interesting. Why did the population decrease? There appeared to be a pattern happening: as things became better for the harbor, amphipod populations increased.

From 2001-2010 offshore diversion was implemented from Deer Island. Treated effluent is now trasnporated 9.5 miles offshore at multiple locations within Massachusetts Bay. A total of 23 of CSOs in operation have been eliminated or have decreased discharge. CSO discharge had decreased 90% in 20 years time (1990-2010).

By 2005 Ampelisca amphipods mats decreased to 0%, apparently no longer inhabiting the sediments of Boston Harbor. Again, interesting that they decreased to 0%!

Amphipod, Leptocheirus pinguis.

Then in 2007, the Ampelisca amphipods were back along with another amphipod, Leptocheirus pinguis. Amphipod mats coveraged 26% of the bottom. Now that seems more like it! Populations increased again and now there are 2 species colonizing the harbor. That is great news because this means the harbor is getting cleaner and more organisms to thrive.

Amphipods mats covered only 5% of Boston Harbor sediments before the Deer Island Treatment Plant was built. As the treatment plant was implemented, amphipod populations increased dramatically to 64% coverage. Amphipod populations started to dwindle when secondary treatment came on line. In 2001, when the offshore diffusers spread clear effluent into Mass Bay, nine miles offshore, the amphipod population went to zero.

In 2007, the Ampelisca amphipods returned along with a new species, Leptocheirus pinguis. Both of these amphipods built tubes in the sediments that became matts covering 26% of the harbor floor.

By 2010, twenty-three CSOs had either been eliminated or upgraded. From 1990 to 2010 CSO discharge into the harbor had been decreased 90%.

Amphipods

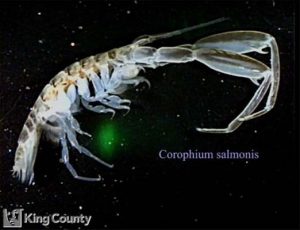

A similar case happened in Vancouver, Canada. The Fraser River Estuary had untreated effluent spewed directly into it- just like Boston Harbor. Eventually, they were able to construct a submerged outfall pipe which completely stopped the pouring of raw sewage into the estuary. Other types of amphipods that are similar to these ones that were involved in studies in Canada are Corophium salmonis and Corophium volutator.

Corophium salmonis and Corophium volutator

Corophium volutator and Leptocheirus pinguis are similar because they both create U-shaped borrows. But, they are all similar because they were able to colonize in sediments that were once sewage filled and contaminated.

Amphipods create sediments into places of denitrification. Denitrification is the microbial process of reducing nitrate and nitrite to gaseous forms of nitrogen, like nitrous oxide (N2O) and nitrogen (N2). Denitrification is a response to changes in the oxygen (O2) concentration of their immediate environment. When the sediments have limited oxygen, the bacteria will use nitrites in the sediment to undergo anaerobic respiration. Ultimately taking nitrogen out of the sediment. Since the MWRA is lacking nitrogen treatment, the amphipods are helping the bacteria clean it up. Amphipods are an ecosystem service in this case- thanks amphipods!

Summary, Boston Harbor amphipods and the facility

Boston Harbor is cleaner than it ever has been. When the Boston Harbor Project was formed the MWRA went to work creating the Deer Island Wastewater Treatment Plant. CSOs were eliminated and their discharge was reduced by 90%. The amphipods of Boston Harbor Ampelisca spp and Leptocheirus pinguis colonized the sediments as the harbor became cleaner and cleaner. Their tube building and burrowing in the sediments made the right conditions for bacteria to be able go through denitrification.

The Ocean River Institute provides opportunities to make a difference and go the distance for savvy stewardship of a greener and bluer planet Earth. www.oceanriver.org