Thursday, August 30, 2018

Far out on the Atlantic Ocean, about 160 miles southeast of Nantucket, the morning light revealed that the sea had changed from cold gun metal gray to a deep Mediterranean blue. Looking out through the pilot house window, I saw a sperm whale. The rectangular black portion above the water reminded me of a railroad box car. The blowhole was forward on the left side of head, on top just behind the perpendicular descent of the whale’s front. The back was flat and smooth no sign of a backbone, no dorsal fin. The expanse of back turned to knuckles that stepped down the tail disappearing into the water.

This was a very different beast than the whales of whale watching, the humpback, fin and minke whales. Their wheeling behaviors had become familiar. Head breaks the surface, followed by paired blow holes, ridged steeply-sided back followed by dorsal fin and sometimes lifted tail.

The sperm whale was still in the water; waves lapped at its square black brow. There was no exhalation of atomized water droplets rising in a diagonal column to fall clear of the whale. This whale was dead.

I turned around in the pilot house to see the captain stripped down to his shorts standing on one foot while maneuvering the other foot into a wet suit held spread by his two hands. The Captain was also a jeweler with an interest in scrimshaw. He was preparing to put on scuba gear to get some whale teeth.

There I stood, the curator of natural history of a Massachusetts museum who had brought a bit more than a dozen patrons on a three-day cruise off the continental shelf on a sperm whale watch. The dead whale was unexpected. And then, the only one who knew how to operate the boat was about to jump ship to take a quixotic swim to pluck teeth from the largest toothed jawbone in the animal kingdom with what looked to me like a Bowie knife. How could things have gone so wrong? How could this distant ocean realm be better managed so one would no longer find one out of three whales sighted floating dead?

A whale first surfaced in my conscientiousness about a decade earlier. The summer of 1974 I was alone on deck of a twenty-seven-foot sailboat, called a Tartan 27. Off the coast of Maine, we were sailing west past Sequin Island Light towards Casco Bay. The main sail and large genoa jib, “jenny,." were filled on the boat’s left side pulling the vessel forward at about seven miles per hour. I stood on the right side of the boat. My left hand was in the middle of the boat on the oak stave of the tiller attached to the rudder in the water. The boat was steered by pushing or pulling the horizontal tiller to turn the rudder. My right hand was on the lifeline at about waist height securing the windward rail like a fence. The line was higher than normal because the sailboat was tipped and I was standing straight. Beyond the gunnels, over the waves, I heard an enormous sigh. Suddenly about 100 feet before and to the right of the boat was a stretch of animal hide that looked to me like a beach where moments earlier had been ocean. It was broad and flat and as long as the boat. Inconceivable. I could not imagine the animal attached to that mirage on the water. Yet there it was.

I cried out, making incomprehensible sounds. A friend down in the galley, looked up the gangway at me and thought I was having an epileptic attack, knowing full well I don’t have that affliction. Climbing to look out over the cabin top he saw only the circle of flat water beside the ship, the whale’s fluke print, where the whale had been. We had overtaken the whale travelling in the same direction. We scanned the sea’s surface looking for another whale’s blow and water-shedding stretch of back, to no avail.

The whale was a right whale. This whale eats plankton caught in its large baleen plates. It swims slower than the fish-eating whales and because of its rate of speed has no need for a fin on its back to stabilize forward motion. I later learned that a right whale had been seen in those waters at the same time as our encounter.

At that time, Peter and I were students at Hampshire College in Amherst Massachusetts. When we returned for our second year, we discovered that a foundation had offered to fund two students to prepare and teach a course at the college. We were awarded the grant and spent the next summer preparing a course on whales and dolphins. We taught the course in the spring of 1976. On April 15th we pulled up to the docks of Provincetown in two vans of students. We had come for the first voyage of a commercial whale watch. Stormy Mayo was the whale spotter. Stormy had recently completed a Ph.D. in marine biology from the University of Miami. His Dad was Charlie Mayo, Provincetown’s best known sport tuna fishing boat captain. I believed Charlie the Tuna on the television commercials was named for him.

The boat captain had been cajoled the previous April by a group of science supervisors of Massachusetts public schools to take them out looking for whales. They found right whales in abundance. Word was people in Provincetown could set their calendars to April 15 by the arrival of right whales. We set our course syllabus accordingly. Fortunately for us, the cold clear weather was most accommodating.

We cleared Provincetown and headed north along the long sandy stretch of Herring Cove beach. Stormy, the Captain and crew were high in the wheel house scanning the horizon. I stood on the foredeck with my classmates. With narrow straight wings a greater shearwater soared wave cap to wave crest, never touching but at time dipping out of our sight. I pointed out the voyager of open oceans. Stormy thought I was pointing out a whale. He was disappointed that I was bothering with a bird that was known for stealing fishing bait from hooks and getting caught on hooks set less than 75 feet deep. Adding insult, I cheerily said if we don’t find whales at least we will have seen fantastic seabirds. We saw red-breasted mergansers, sooty shearwaters, greater shearwaters, and gannets before finding right whales, humpback and fin whales.

About two decades later, I returned to Provincetown for a whale watch on a Dolphin Fleet boat with my three teenage sons and an exchange student from Brittany France. Powering north past Herring Cove I spotted a greater shearwater. “Look,." I said, “there’s a greater shearwater they wander the ocean and nest in Tristan de Cunha in the Southern Atlantic Ocean.." “Look,." boomed the loudspeaker, “there’s a greater shearwater they wander the ocean and nest in Tristan de Cunha in the Southern Atlantic Ocean.."

“Look,." I said minutes later, “there’s a gannet, note how they are like a flying cross, pointy on all four ends.."

“Look,." came again the loud voice from on high, “there’s a gannet, note how they are like a flying cross, pointy on all four ends.."

Three times my seabird comments were repeated word for word over the loudspeaker. Dads have never sounded so good. Turns out that Stormy had sent two of his crew on one of my whale watch voyages for the New England Aquarium. They wrote down everything I said about seabirds, and my words had been said on Dolphin Fleet voyages verbatim ever since.

Whale watches sailed with a narrator who gave passengers more than the names of animals. Each bird was given a handle, something unique that would make the animal memorable. Shearwaters are interesting because they wander the ocean. They are seabirds never seen on land. They are strange to us land dwellers. Shearwaters are remarkable because they fly thousands of miles in both the North and South Atlantic Ocean. When the wind has dropped shearwaters sit on the water like strange ducks. To take flight, unlike gulls, they must labor flapping narrow wings and running on the water. It is easy to empathize with shearwaters and think of the Wright Brothers’ efforts on the sands of Kitty Hawk. On whale watches the greater shearwater with striking black cap and gray cheeks became familiar. Seabirds are harbingers of humpback whales because both eat the same fish. Sight a bunch of bird roiling like a tea kettle over a piece of ocean and likely there are humpbacks feeding below.

Years later Cory’s Shearwaters arrived to fish Stellwagen Bank, to join the whale foray for sand lance, herring and mackerel. Corys lack the black caps of the greater shearwater. Instead they sport a gray hoody. Corys are larger than the greater shearwater. The different shearwaters flew and dove together in pursuit of the fish being churned up to the surface by whales. Cory’s shearwaters stood out from the greater shearwaters like Big Bird in a flock of yellow ducks. The smaller the shearwater the deeper they dive. Sooty shearwaters dive deepest and fishermen have learned to bait hooks more than seventy feet deep to not catch a sooty.

As narrators, our goal was to introduce people to the diversity and unfathomable complexity of ocean ecosystems. Waves on the sea surface may look the same yet the ecosystems below change. Traveling from deep water up onto Stellwagen Bank is as dramatic a change as stepping off of the turf of a soccer field and sinking into the muck of a salt marsh, carpet of grass replaced by soft sand and little crabs with a big claw like a fiddle and little claw like a bow that pinch between one’s toes.

Stellwagen Bank is a patchwork of at least four ocean floors. The muddy bottoms are the preferred habitat of stalked sea anemones and Acadian redfish, known in restaurants as ocean perch. The sandy ocean floors are where monkfish settle in, wave their forward most pectoral fin to lure prey into jaws that remind me of a set bear trap. The gravel floors are the preferred haunts for ground fish, cod, haddock, pollack and hake. And then there are the boulder reefs where wolfish den. Kelp forests, mussel beds, even shipwrecks, enhance the textures of seascape we call Stellwagen Bank.

Each ocean animal has a place, inhabits a niche, in wildlife communities, a place in the web of life that makes up dynamic ocean ecosystems. Watching a gannet fly is marvelous. The white flying cross with a six and half foot black tipped wingspan, pointy with head and white tail. The power of the gannet’s wing lift is accentuated by slow deliberate strokes. Gaining heights greater than 100 feet, the bird stalls, folds wings in and plunges vertically downwards cork-screwing to strike water with a resounding “thunk,." like an arrow into a hay stuffed target. Height and speed propel the bird deep into the water penetrating a school of fish. Observing gannets flash and flare white the seascape, erupting spray like the blown spume of whales, is to come to know a bird worthy of a healthy ocean.

Each ocean animal has a place, inhabits a niche, in wildlife communities, a place in the web of life that makes up dynamic ocean ecosystems. Watching a gannet fly is marvelous. The white flying cross with a six and half foot black tipped wingspan, pointy with head and white tail. The power of the gannet’s wing lift is accentuated by slow deliberate strokes. Gaining heights greater than 100 feet, the bird stalls, folds wings in and plunges vertically downwards cork-screwing to strike water with a resounding “thunk,." like an arrow into a hay stuffed target. Height and speed propel the bird deep into the water penetrating a school of fish. Observing gannets flash and flare white the seascape, erupting spray like the blown spume of whales, is to come to know a bird worthy of a healthy ocean.

Further out into the Atlantic Ocean across Georges Banks to the far side where canyons incise the continent to plunge more than 10,000 feet deep are where the sperm whales live. They dive into the inky blackness in pursuit of giant squid. They easily stay underwater for 45 minutes. The crush of ocean pressures that increase with depth compresses their lungs completely. Sperm whale muscles have a high concentration of myoglobin, a molecule that binds more oxygen to pick up on the supply where lungs fail. Myoglobin turns the whale’s muscles black and makes sperm whale meat inedible. Sperm whales dive and surface swiftly without suffering the bends. They avoid the rapid release of oxygen, a fizzing into the blood, because the lungs have been emptied of air.

I had the good fortune to traverse the deep sea canyon haunts of sperm whales in 1980. I was working as assistant scientist onboard the Research Vessel Westward for Sea Education Association out of Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Twice that summer we sailed through canyon waters. Each time we saw sperm whales. Years later when I was Curator of Natural History at the Peabody Museum of Salem, now the Peabody Essex Museum, I mentioned my encounters with sperm whales. On Fridays, in the basement surrounded by ship models and vast shelves of nautical paraphernalia and marine artifacts, the men who volunteered to mend models pushed together work benches and tables, covered them with a red checkered tablecloth, and pulled up chairs to gather round with their bagged lunches. Needless to say, they were most interested in seeing a sperm whale on the far side of Nantucket.

How they were most interested worked itself out. We chartered a commercial boat out of Gloucester. It was built for recreational fishing, jigging over the rail for cod and haddock, pollack and hake, the bottom fish (demersal) of Georges Bank. Some brought their wives and a few other museum folks joined the small expedition. We set out for a three-day voyage in June when the weather forecasts were most favorable, a day and night out, day on the canyon, and a night and day back.

I was alarmed to see the boat captain preparing to swim with the dead whale because losing a person on a whale watch would more than tarnish my reputation as a whale watch operator. We were about one hundred miles southeast of Nantucket and much further from the home port of Gloucester. On the high seas is not the place to talk about laws and the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Thinking fast, I said that the whale was like a thermos bottle filling up with decomposing methane gasses. One touch and it was likely to blow up and then there would be sharks everywhere. The captain proceeded to step out of wetsuit and put his clothes back on. We went on to watch two very alive sperm whales surface, blow, and dive.

Out in New England’s last vast wilderness, it was very disconcerting when we observed three sperm whales, one was dead, and this was only my third visit to the canyon waters. A dead whale floats because decomposing gases cause swelling and buoys the beast. Eventually the gas pressure becomes so great that the skin lets go, gas vents out, and the animal sinks to the bottom of the ocean. Sharks can expedite the sinking of dead whales.

I feared we humans were responsible for this death, likely a ship strike. The crew of the big vessel striking a whale likely never understood, if heard at all over the rumble of engines, the bump in the night. We never saw another ship that day on the canyon. How could we better manage, take better care of a distant ocean realm?

The answer to protecting a vast ocean place began at the smaller, local, scale of Salem Harbor. I discovered right scale of management in a new maritime exhibition at the Peabody Museum on the first floor of the historic East India Marine Society Hall. The dark beams spanning the ceiling gave the space a feeling of being below decks. A nautical chart was set out under glass. I was surprised to see on the chart written across the ocean floor between Marblehead and Beverly “Salem Sound.." I had sailed these waters and spent hours studying an earlier edition of this chart that did not name the bioregion. We knew this area broadly as the North Shore of Massachusetts Bay. People said they lived on the North Shore meaning somewhere along an expansive and varied shore from Revere next to Boston, Saugus iron works, Lynn with Red Rock and Nahant, far east to Gloucester and Cape Ann.

Salem Sound is embraced by just six municipalities. Marblehead reaches up from the South. Salem is adjacent. Peabody, Danvers, Beverly, and Manchester-by-the- Sea complete the arch with a couple of granitic islands corking the Sound. Here was a bioregion of a manageable scale for the local museum curator of natural history.

I was most surprised to learn from the state coastal zone management agency that the city of Peabody is on the coast. There is a smidgeon at the mouth of the Danvers River, tonguing seaward between Salem and Danvers. I led a walk to the coast of Peabody and it made the front page of the local newspaper. I looked like Moses, a bearded guy with hair leading a group of people into a tall stand of phragmites, tall nine-foot-high Egyptian marsh grass light brown with fuzzy tasseled tops. In Peabody to reach the sea one must part the grasses.

It was crucial to include Peabody as part of the Sound because everything that went into the ground or the North River ended up in Salem Sound. The sewer lines all ran to the South Essex Sewage District in Salem on the shore. Silver nitrate from the Polaroid plant in Peabody was flowing through the treatment plant into the harbor. The president of the Salem Bank was kind to host me and invite the CEO of Polaroid’s Peabody facility to his office. I brought a carousel of slides of Salem Sound, a projector and served tea off of a tea set from the museum (not a tea set of the collections.)

My point to the CEO was our quality of life is tied to the health of the harbor. Please do not put chemicals down the drain. The sewage treatment plant cannot remove them from the waste stream going into the harbor. The CEO listened and stopped putting silver nitrate down the drain. He found that recovered silver nitrate and other chemicals could be reused and ended up saving them money. Harbor saved.

The challenge of collaborative management for Salem Sound was that the municipal governments were so different from each other. At the large end of the spectrum were the cities of Salem and Peabody with mayors and selectmen. Beverly was a different governance. Danvers had a Town Manager. One of the three Conservation Commissioners was the contact for Manchester.

Tea-cup diplomacy became lunch meetings over sandwiches at the Firehouse Diner in Salem. A bank employee, a lawyer, a manager from Polaroid, and a consultant with Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management (the one who knew that Peabody was a coastal community) and I launched Salem Sound 2000, a bioregional management initiative. It was 1990, we had a vision of a cleaner Sound and set out to chart a course to get there in ten years. Parochial attitudes of not my problem when it’s worst over there had to be replaced with a can-do, proactive attitude. To improve the life of the bioregion, the six municipalities needed to come together and work in concert.

I met with each municipality’s representative to learn about their Salem Sound challenges and issues. An issue of common concern was yachts pumping their sewage into the harbor. The state law was to clear away three miles offshore into federal waters before pumping. Marblehead has the most yachts crowded into a rock-bound cove. Marblehead did not want a pump out facility for their boats. They said Salem should instead provide pump out facilities, be the toilet bowl for yachts, because that was where the South Essex Sewage District facility was located. It is most unlikely that a family out for a sail was going to turn inland to tend to the unspeakable. It is very easy and convenient to discharge waste into the ocean.

Individuals from the six municipalities met together, worked with our Coastal Zone Management agency, and were awarded a grant from the EPA to purchase a pump-out boat. Each week day the “honey boat." pumped a different town’s yachts. Operating expenses were paid for from mooring fees.

One bioregional management success led to more successes because now the different town representatives knew each other. Volunteers stepped up and their numbers grew with the thrill of working together around mutual interests. The collaborative management continues today as Salem Sound Coastwatch, monitoring, addressing challenges and finding solutions.

I turned my attention to Boston Harbor, served as president of Save the Harbor/Save the Bay, and was employed as Curator of Education at the New England Aquarium.

In 1996, Congress surprised the nation by creating the Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area. In keeping with fiscally austere times, this was the first national park where Interior owned no property. Instead properties owned by nonprofits, city government, state government and federal government (the Coast Guard) would be managed in a two-tiered partnership. The Partnership consisted of eleven big-wigs, including the National Park Service, Coast Guard, Mass Port (Logan airport), Metropolitan Water Resources Authority (Deer Island sewage treatment facility), Department of Environment, and City of Boston, plus two representatives of the Advisory Council. The Advisory Council was composed of four representatives from seven interest groups (28 members) that included municipalities (Quincy, Winthrop, Hull, Chelsea), businesses, education, conservation groups, and Native American tribal nations.

To participate in Boston Harbor big-scale bioregional collaborative management, I wanted the skills and knowledge to understand why initiatives either worked or failed. The Switzer Environmental Fellowship program was good to support these endeavors, and I enrolled in a new doctoral program at Antioch New England University.

A Wampanoag Aquinna from Dartmouth, Massachusetts, represented Native Americans and I, representing most everyone else on the Advisory Council, were appointed by Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt to serve on the Partnership. It took four years of many meetings to reach unanimous agreement on the General Management Plan. My dissertation committee had me work a bit longer to complete the PhD in 2002.

An early success for the Partnership was making publicly accessible Boston Lighthouse, the oldest continuously operating lighthouse in North America. It remains the only one still manned by the Coast Guard. With plenty of navigation and rescue work to be do, the Coast Guard had no time to show visitors about the island. Fortunately, the Friends of the Harbor Islands wanted nothing more.

Little Brewster Island is a tumble of glacial erratic boulders mounded on top of bedrock outcroppings – not conducive for landing a boatload of visitors and sight-seers. Attending Partnership meetings, the commander got to know the MassPort representative, who majored in ecology. MassPort happened to have a removable dock that they were willing to loan to the Coast Guard. A removable dock addressed all their concerns. Instead of mounting all kinds of engineering hurtles to build a dark capable oif withstanding whatever the Northwest Atlantic threw at it, the Coast Guard could let go anchor lines, pull in ramps, and simple pull the dock away from the shore to a more sheltered anchorage area. With the national Coast Guard, the state MassPort and local Friends group working collaboratively, the Boston Harbor Islands national park was able to offer a magnificent public amenity. Going to the Lighthouse became emblematic of the advantages to managing in partnership with one another.

The Boston Harbor Island Partnership was the exception. Most agencies operate within their own spheres of responsibilities and authorities. It was like a bunch of grain silos, standing separately with communications going up and down within each. A small town at the head of Massachusetts Bay called this age old practice into question. Winthrop had lost sand from its beaches. It had reverted back to its natural state of muddy shore. For three years the town called on the state for more sand. Finally, the department responsible for sand mining spoke to the town. They would move sand excavated from a designated ocean floor place and deposit it on Winthrop’s beach. At the meeting a member of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries spoke up saying no can do, the area to be mined was where commercially valuable fish eggs were laid. Winthrop was not happy to see beach plans go back to drawing boards for indeterminate months due to no fault of theirs.

The state needed to get its agencies working together better before it could properly manage ocean and coastal issues for municipalities like Winthrop. In 2007, legislation was introduced for a Massachusetts Oceans Planning Act. I was contracted to educate, engage and build a Massachusetts constituency supportive of collaborative ocean area-based planning. The collaborative planning act was enacted in 2008.

Once mandated to work together, each agency mapped out what ocean floor areas they deemed sensitive and should not to be disturbed. All the maps could be overlaid to show an entrepreneur where developments could be placed with least objections from any agency. This enabled an internet cable company to propose a line to Martha’s Vineyard be buried beneath sensitive habitats to close to shore. Out in Buzzards Bay the proposed cable route jogged northeast and then southeast to avoid a sensitive area in the middle. When the cable company sat down with each agency many specific concerns had already been met. Remaining differences could more easily be addressed.

In 2010, President Obama created the National Ocean Planning Council. He was encouraged that in Massachusetts state agencies did not give up any authorities when working in collaboration. Massachusetts was demonstrating that collaborative decisions were better informed, more robust, and more capable of surviving the tests of time.

Eight regional ocean planning bodies were called for. The Northeast Regional Ocean Council was first assembled because of positive experiences in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. The Mid-Atlantic Regional Ocean Council quickly caught up with the Northeast. All other regions took a wait-and-see attitude.

The Northeast ocean planning council is a remarkable assemblage of representatives from eleven federal agencies, eleven state agencies from six New England states and ten tribal members (The Aroostook Band of Micmacs, Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, Mashantucket Pequot, Mashpee Wampanoag, Mohegan, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Narragansett, and Wampanoag Aquinnah). The meetings were very productive for individuals with opportunities to talk with colleagues across agency and state lines. Most memorable was a presentation by a Woods Hole fisheries scientist and Mashpee Indian Chief alternating perspectives and observations.

There is a parable of stone soup where the variety of ingredients provided by a diversity of community members result in an excellent soup that is nourishing for all. Being very place-based, the ocean planners were making clam chowder seasoned by stakeholders. The New England Ocean Action Network (NEOAN) is composed of individuals and organizations from the region’s ocean community, educational and research institutions, fishing industry, clean energy field, and other ocean users and industries. NEOAN bird-dogs and advices the regional planning council.

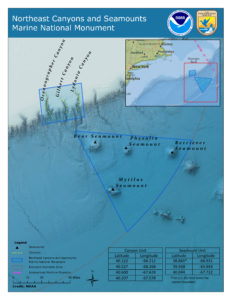

Four years of council meetings were well attended, shared interests found, a remarkable portal of vast amounts of information was taking form, and a working consensus for a general management plan was being built. Then in August 2015, a small group of conservation organizations called on President Obama to carve out of the collaborative efforts 4800 square miles of ocean for a national marine monument. The President was to use the Antiquities Act to go around Congress to create a marine protected area for the waters over three deep sea canyons and all four Atlantic seamounts southeast of Georges Bank. Ocean planners and federal legislators in Congress felt betrayed. It felt like a game changer. Why collaborate if constructive meetings and consensus building could be turned into an elementary school game of Kick-the-can, where planners and fishermen felt more like the can than players.

There was precedence. Two previous presidents (Clinton and Bush) had created national marine monuments. This was different because it was after the President had created also by executive order the National Ocean Planning Council. Recognizing this my organization, the Ocean River Institute, launched a campaign in concert with ocean conservation groups but with a brighter tune of calling attention to the ocean conservation work of the Northeast Regional Ocean Council and not wailing about the overfishing that happened before the Magnuson Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976.

For a 100 years since 1916, National Parks have been well managed by one agency, the Department of Interior. An ocean realm, however, is much more complex, and with many more uncertainties than, for example, Yellowstone National Park. As with the killing of a sperm whale it takes more than one to manage. In the open whaleboat there is a mate steering, a harpooner in the bow and a crew rowing. To approach a whale took skill and finesse because whales use sound to navigate and have better hearing than do we. The clunk of a wooden bailing pail on wooden floor boards, or even the splash of an oar, could (as whalers traditionally said) “gally." the whale, causing it to dive and disappear. Once the whale was harpooned two crew members were responsible for dowsing the wooden loggerhead with water while the line smoked round it. Everyone had to make sure the line ran our clear of limb or gear. Ocean management is like that; it a take a boat load of agencies and groups with much research and preparations to be sure the ecosystem is running clear without capsizing, and hold on for the ride.

There must be strenuous pulling of oars to move the Leviathan of ocean problems into a comprehensive and responsible ocean management. The course to a healthier ocean is fraught with ocean dead zones, harmful algal blooms, increasing ocean acidity and shifting currents. The restoration of individual populations, diverse communities, and robust habitats are trying work.

To deconstruct the open ocean into take and no-take zones is the antithesis of systems thinking and ecosystem-based management. The ocean is dynamic, affected by many factors at once. Where herring shoals are this year may not be where herring shoals are next year or a decade later. Where the forage fish are the predators follow and so goes the ocean ecosystem.

Out at the deep sea canyons, Loligo squid, whiting and mackerel are being sustainably fished with mid-water trawls and purse seins worked by pairs of boats. In the ribbon of ocean less than 500-meters-deep that wraps the canyons, lobsters are caught. There is no dredging of scallops or other shellfish. Out over the seamounts is gill netting and long-lining for swordfish, yellow fin and skip jack. It makes no sense to remove this portion of ocean from management as if using a cookie-cutter incising a piece from the vast expanse of sea.

In September 2015 in Washington, I met with most of the members of the New England Congressional delegation to vet my letter. The president should recognize by monument designation a nearly pristine place in the most heavily fished waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Rather than complaints of overfishing in this place, a place where cod, haddock, pollock, hake, and other delicious demersal fish are not fished, kudos should be given for the best managed fishery in the world. Here’s a wondrous ocean place where square-headed sperm whales dive deep to erupt the sea surface like a freight train, where shearwaters row with stiff wings the wind-swept air over white-capped waves.

While others rallied their members on social media, the Ocean River Institute went to the Cow Palace in San Francisco for the Green Festival. Ocean advocacy is personal. It is in the eye contact, watching expressions, hearing intonations, that the work of ocean conservation is done. While thousands of ORI subscribers had already signed our letter and hundreds wrote thoughtful comments, at the Cow Palace individuals, couples and families picked up a clipboard. The letter had two paragraphs, one about the deep sea canyons and seamounts, and one about the planners including names of the ten tribal nations. Instead of a third paragraph were five lines on which people were invited to write. Some wrote about the place and some wrote about the process. My favorite comment was written by a woman from San Jose, California named Gwen.

We’ve gone to other planets, to space, literally out of this world and discovered the coolest things around. It’s amazing! But the ocean is one of the least explored places that we haven’t really gone deep down to which is funny because it’s literally right there! There is so much to see, so much to discover; it is only fair to recognize a place that holds so much potential! I mean can you imagine the sort of crazy creatures that live under there that we don’t know about yet!

In September 2016 President Obama created the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts National Marine Monument. The Secretary of Interior would govern in equal partnership with the Secretary of Commerce. The Secretaries must listen to all federal agencies with any jurisdictions touching on this ocean place before making any decisions.

Conservationists cheered and fishermen fumed. Banned were trawling and purse seining for Loligo squid, whiting and mackerel. There would be no longlining/gill netting for swordfish, yellow fin and skip jack, and no dredging (not possible off the continental shelf). Less than two percent of the six fish stocks were caught in the monument area. The heat of these arguments were short on substance and all about the principles to fish or not to fish.

The lobster fishery, however, in this area is worth more than the other six combined. Fourteen lobster boats work in the monument from Rhode Island, Massachusetts and down the Lamprey River from New Market, New Hampshire. Lobstering was permitted to continue unabated for seven years. While the media focused on the fishery closures, as if cod was involved, which it was not, conservationists were furious that lobstering was permitted. They blamed a few Senators, two who are outstanding on ocean conservation issues, for caving and failing to create a no-take federal area.

Later in September 2016 in Washington, D.C., I had just completed a meeting with Senator Ed Markey’s ocean expert and come out of the Hart Senate Office Building into the bright of day. At the street corner was the back of a tall lean man in a black suite with familiar gray hair. Senator Markey stepped off the curb to cross over towards the Capital Building. I caught up and matched his long strides. “Senator,." I said “thank you for letting the lobstermen continue to fish the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts National Marine Monument.."

“I could only get them to stay for seven years,." came the forlorn response.

“Senator,." mustering my best Markeyism, “not since the Mariposa Battalion went into Yosemite has any user been permitted to stay and continue working in a national park area. This is huge.."

Later in the evening at the Ocean Champions reception the Senator entered the crowded room. He saw me, smiled, and gave two thumbs up. The accomplishment was fleeting. His work continues moving the fishery council to windward towards a sustainable fishery for all 232 commercially valuable American fish stocks (only 28 fish stocks to go) with better monitoring, less bycatch, and more federal funding.

Unable to see beneath the sea’s face, for the most part, there is no more immediate reassurance of a healthy ocean than a working lobster boat. These deep water trappers are the last undersea canyon rangers. With intimate knowledge of this ocean realm, they are the eyes on the resource. At no public expense, these watchmen serve far offshore on a continental frontline under assault by the effects of Global Warming and increasing ship traffic.

The Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument, this wondrous ocean realm of deep sea canyons, home of the sperm whale and cold water corals, is today with better known and managed then when I found a dead sperm there. Yet, the death of whales by ship strikes will continue in the absence of deep sea canyon rangers. When in the presence of whales, ships must reduce speed to ten knots. Under watchful eyes of rangers, ships will be motivated to plot a different course to avoid collisions with marine life in our national monument area.

The Ocean River Institute provides opportunities to make a difference and go the distance for savvy stewardship of a greener and bluer planet Earth. www.oceanriver.org